A brief foray into what archaeology looks like in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The average kiwi, when questioned about archaeology in Aotearoa New Zealand will more often than not shrug their shoulders, mumble about pā and goldmines and then go on to say that surely archaeology is not a thing here? (something I have discussed in another blog here) After all, it’s not like in Europe or Egypt, is it?

So, lets break that down…

First, archaeology as a subject is defined as the study of the human past, where human modified/made objects and sites are studied in order to better understand our past. Aotearoa New Zealand has a human past and thus, yes there is archaeology to be studied. Interestingly, the country’s relatively short human past has meant that it is in a unique position to better understand the short term and long term effects of environmental changes. Not only how they have changed but also what factors have contributed to this are important questions when faced with an uncertain future. Such studies are often conducted using archaeological data sets. Excavations on Ōtata, an island in the Hauraki Gulf, has produced a significant data set allowing for comparisons with present day data. Read more about this here.

Archaeology as a subject incorporates a wide variety of disciplines from math’s, biology, physics, chemistry, art, history, geology and geography and much more. Because of this it is dynamic discipline, always changing and adjusting ideas as new information or techniques come to light.

The fact that archaeology here in Aotearoa New Zealand has a dedicated association (the New Zealand Archaeological Association), as well as laws protecting archaeological sites and taonga; in addition to a government agency (Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga) and numerous archaeological contractors would all suggest that archaeology is very much present in our small corner of the world. As mentioned in a previous blog there are over seventy thousand archaeological sites recorded here – and these are just the ones we know of…

The New Zealand Archaeological Association

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

Second, our archaeology may not be about romantic, mystical ruins or great depths of time, but it is all around us if you know where look. In its most basic form (because this is a blog and not a textbook) archaeology can be divided into two columns – sites and artefacts. It is perhaps important to note here that archaeology, history and cultural heritage are not separate subjects but are deeply intertwined, especially so here in New Zealand.

The first humans to arrive here were the Polynesian ancestors of the Māori, this is not the place to discuss their arrival except to say it is generally agreed that it happened around 800 years ago. Some of the earliest radiocarbon dates are from around the mid to late 1200s but that’s not to say people weren’t here before that, only that this is currently the earliest dates we have. At this point I should mention that there is no proven evidence for non-polynesian settlement of Aotearoa prior to their arrival.

In 1642 Abel Tasman shined a brief light on the country and much later James Cook’s survey of New Zealand (1769) shone an even brighter light – the British (and the French and a few others) were not averse to new opportunities. The first to take advantage of this new land were the sealers and whalers and by the early 1800s the first settlers had arrived, usually missionaries with notions of spreading the word of God. Farmers, merchants, miners and anyone with an eye to making their fortune soon followed. All of whom left their mark archaeologically.

As mentioned above, the archaeology of Aotearoa can be divided into either sites or artefacts. A site is any place that has been used or modified by humans for any reason. An artefact can be defined on the same principles – an object that has been used, modified or created by humans. In this blog I will be touching upon some of the sites which can be found in the landscape of Aotearoa New Zealand (the subject of artefacts is perhaps too large for a simple blog).

Lets begin in ‘prehistory’ before the arrival of the Europeans…

Middens – perhaps one of the most common archaeological sites known around the country, these sites present themselves as piles of broken shells and relate to the māori settlement of an area. Middens are useful to archaeologists as they can tell us a great deal of what resources were utilised, what the environment was like and they can provide material for dating (bird bones and or charcoal). They can be an archaeological site on its own or part of a larger archaeological site such as a pā.

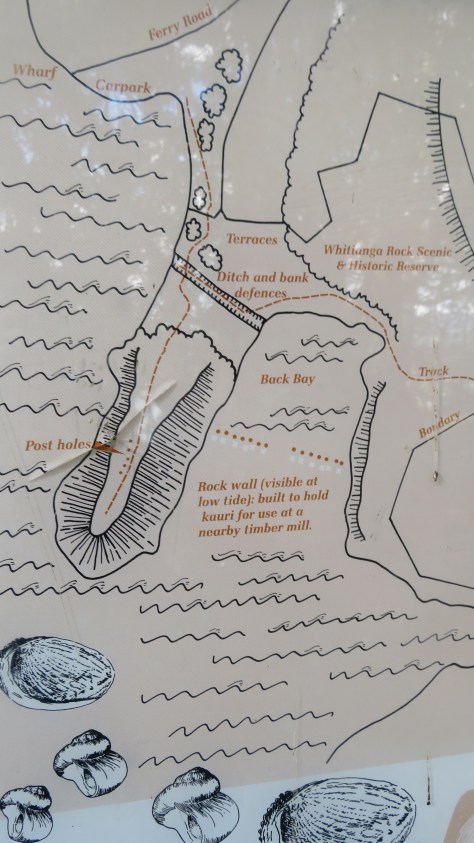

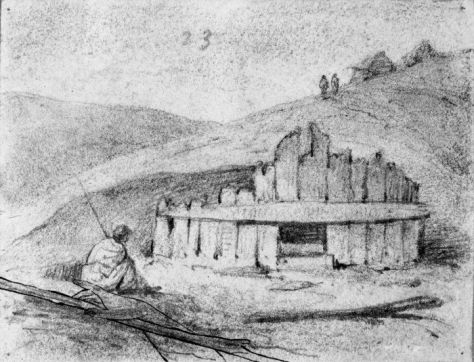

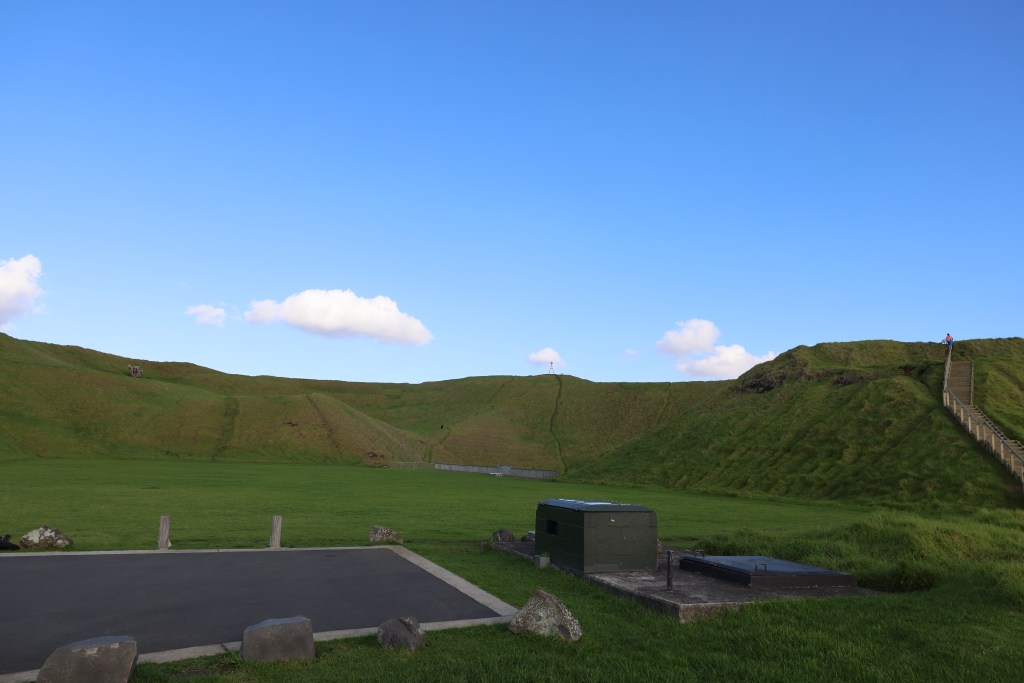

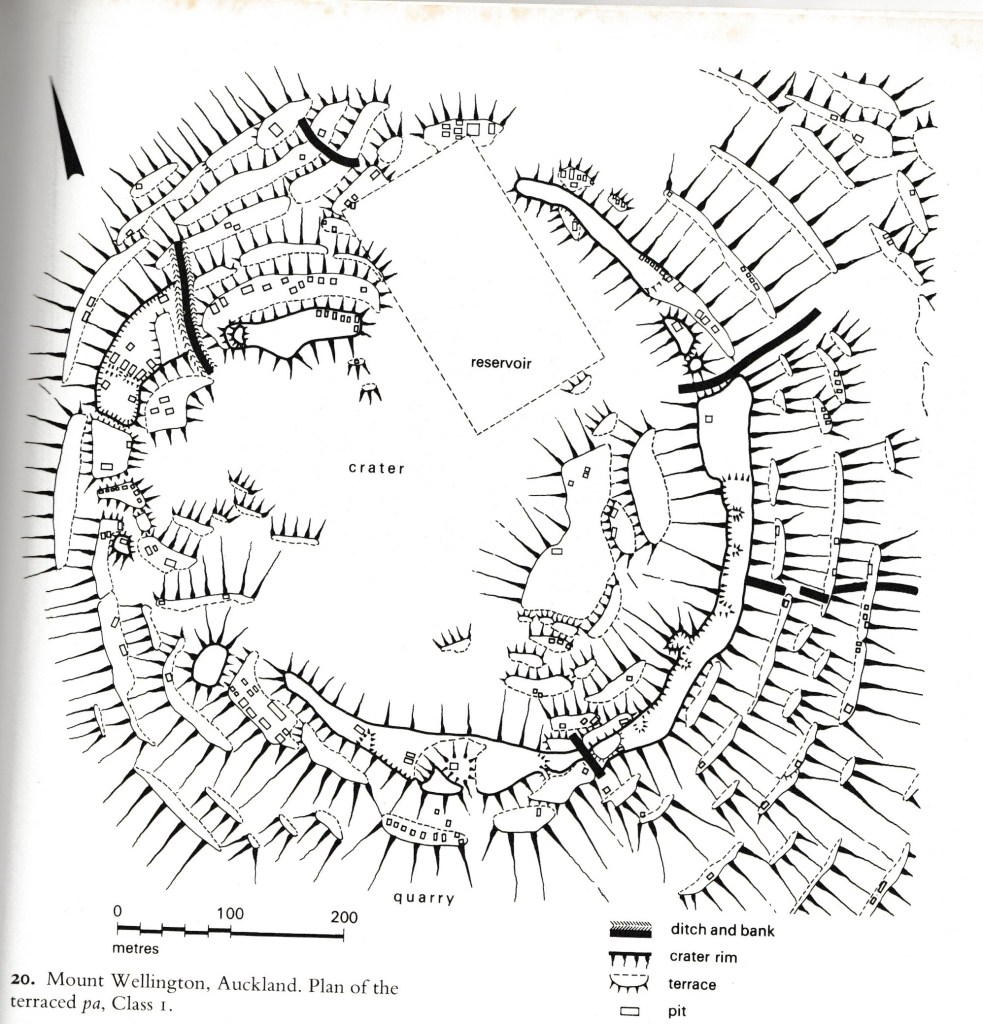

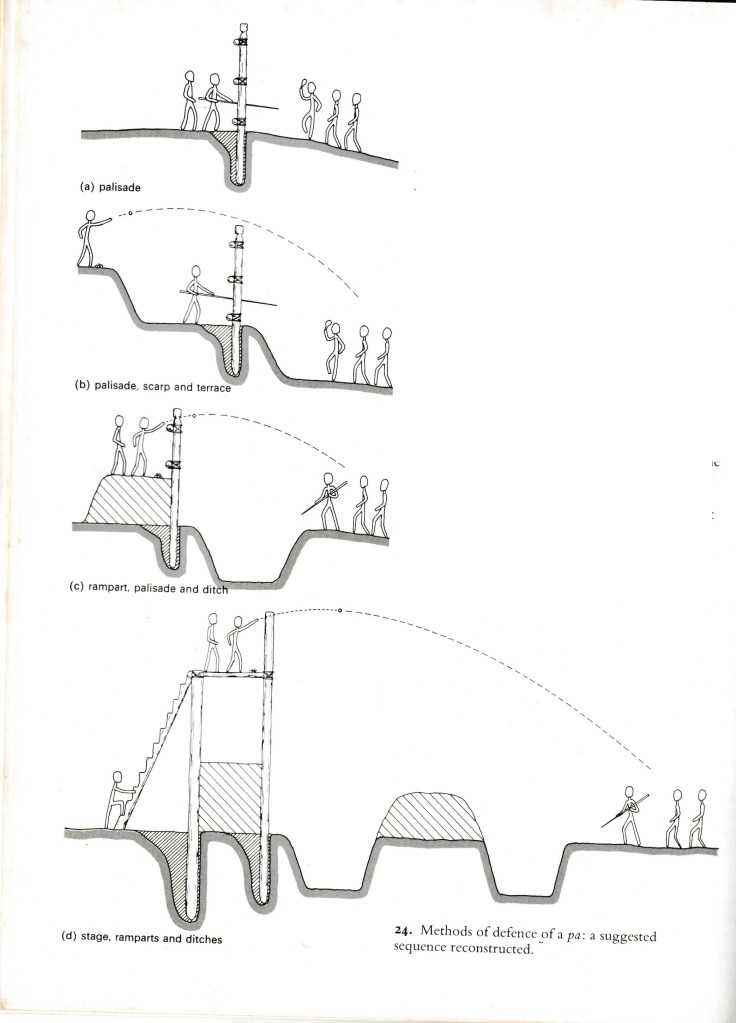

Pā – these are essentially defended settlements, most are found on high ground but there are examples of pā being found on low ground. The necessary element is for the site to have banks, ditches and evidence of palisading. Some pā can be complex sites with large numbers of banks and ditches covering many hectares others are much simpler. It is generally assumed that pā were used as places to retreat to in time of conflict and whilst this is a part of their story, it is not the whole story. The history and purpose of pā depends on the where and when. Each site needs to be considered within the wider physical and societal landscape.

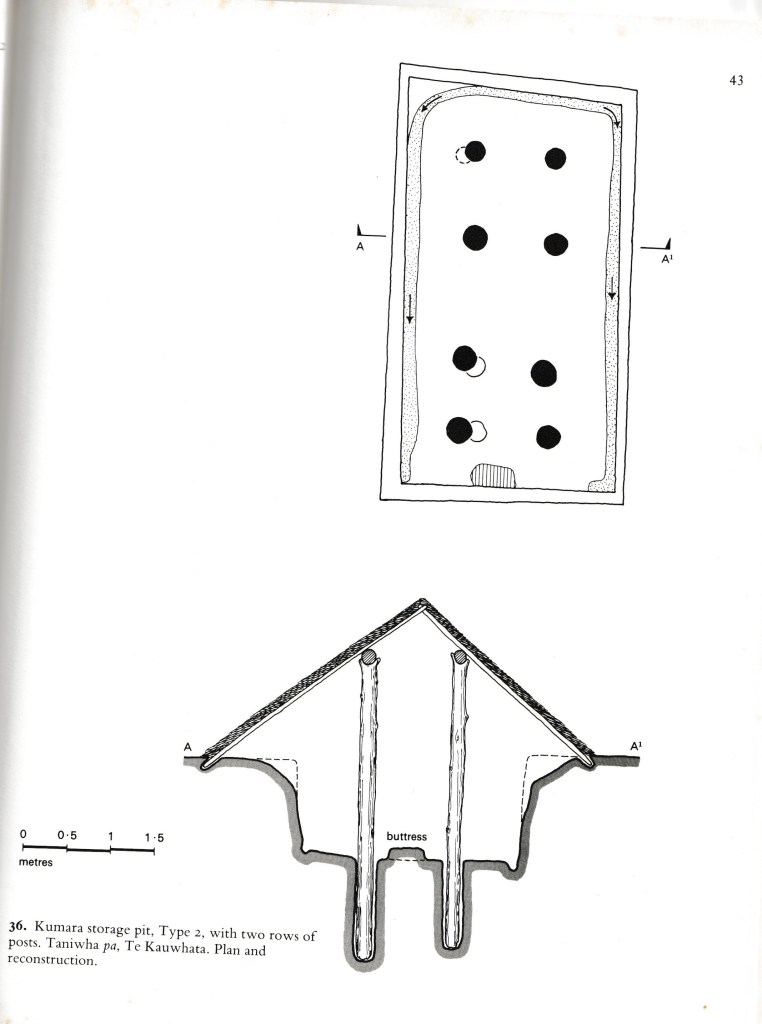

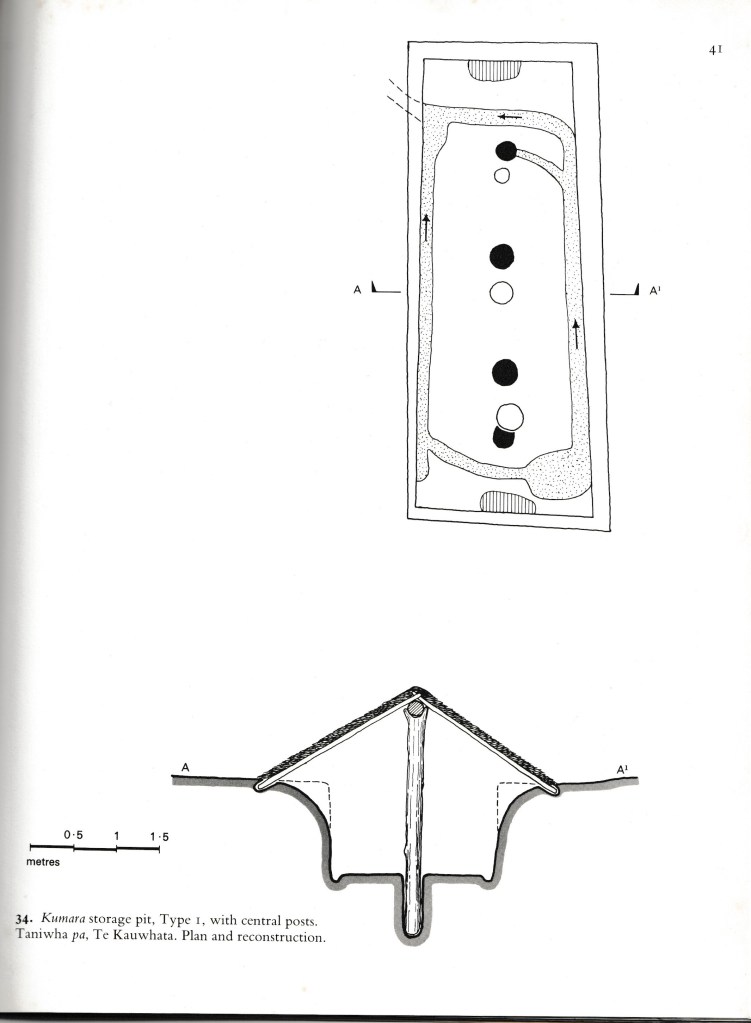

Kainga – unlike pā these are ‘undefended’ settlements or places. They can be either permenant or temporary, (the latter also known as ‘camps’) and can include a wide range of activities, not just places where people lived. Within this category a range of individual features might be found from postholes for wooden structures (houses, storage, fences), cooking areas, storage pits, middens and open spaces.

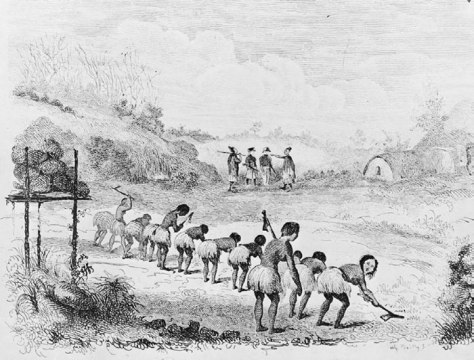

Gardens – horticulture was an important part of the economy for māori and continued to be so beyond the arrival of the Europeans. Evidence on the ground for gardens can be seen in clearance of stones and rocks from an area, often creating low stone walls. In the Auckland area the best example of this can be seen at Ōtuatua Stonefields in Mangere.

Rock Art – almost 90% of known rock art is found in the South Island, it can drawn (using charcoal or red pigment known as kōkōwai), painted, carved, cut or scraped from rock. The designs vary but can include people, birds, dogs, waka, geometric designs and occasional mythical creatures such as taniwha. The Te Ana Rock Art centre near Timaru conducts tours of the nearby rock shelters to view the rock art.

Burials and urupā – Māori buried people of high status close to settlements, then disinterred the bones and placed them in secret locations. Burial sites are tapu (sacred) and should not be disturbed. These practices changed in the late 19th century, when European-style urupā or cemeteries developed near marae. Archaeologists often refer to kōiwi and these are when human bones are found in an archaeological context either during excavation or accidentally (ie eroding from cliff or dune).

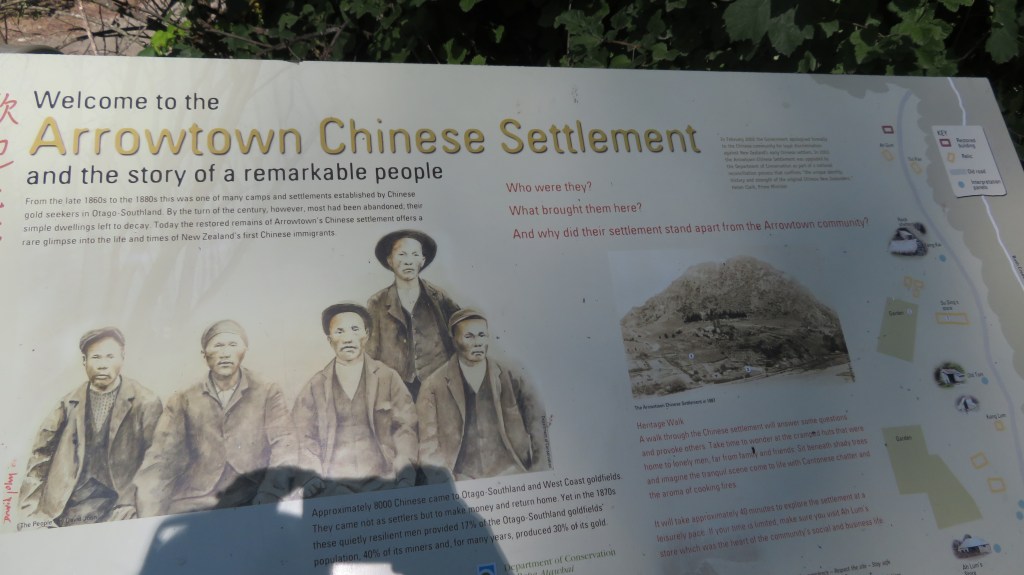

The arrival of Europeans created a whole range of archaeological sites, broadly speaking they can be divided into settlements, industry, roads and infrastucture, dump/midden sites and conflict.

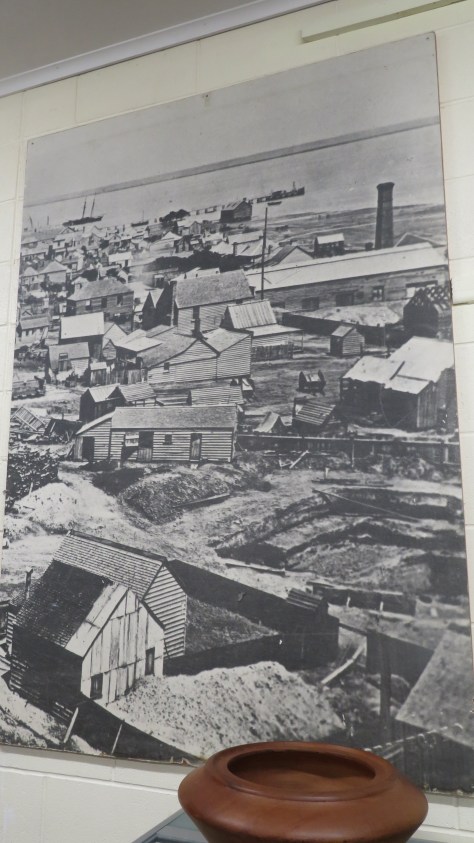

Settlements – the name says it all, these are places were people lived and they can be large as a town or small as a single farmstead. Depending on size settlement sites will invariably include a number of other features which can be classed as sites, such as wells, drains, out buildings, churches, schools, hospitals, shops, inns, roads, gardens and much more. Many of these sites are still standing and usually come under a heading of ‘buildings archaeology’ or ‘heritage archaeology’. After the earthquakes of 2010/11 in Christchurch a vast amount of archaeological work was done ahead of the rebuild. Out of this The Christchurch Archaeology Project was born where the information and stories that emerged of Christchurch’s past could be made available to everyone.

Above shows the site of the Te Rongokaupō village on the Old Coach Road, Ohakune. A once thriving settlement now only humps and bumps in the landscape.

Industry – these are sites which include places that were worked by people to gain resources of some kind. Whaling/sealing stations are some of the earliest sites in this category. Mineral extractions left a range of site types from mines shafts, pumping stations, sluice gullies, out buildings, ore processing plants and more. Industrial sites such as these would often be associated with a nearby settlement which had evolved from a shanty town to a fully fledged and ‘proper’ town. In addition, other forms of industry such as milling (timber, paper and flour), brick kilns, lime kilns, gumdigging, breweries and iron works to name a few leave their mark on the landscape.

Roads and infrastructure – in the early days of Aotearoa New Zealand, the easiest way to travel was via water (this also goes for the period before European arrival). Wharves, jettys and quays are all evidence of this, looking at the placenames of early European settlements near the coast or rivers and the word ‘landing’ can often be found indicating a site where boats and the like would ‘land’ people and products.

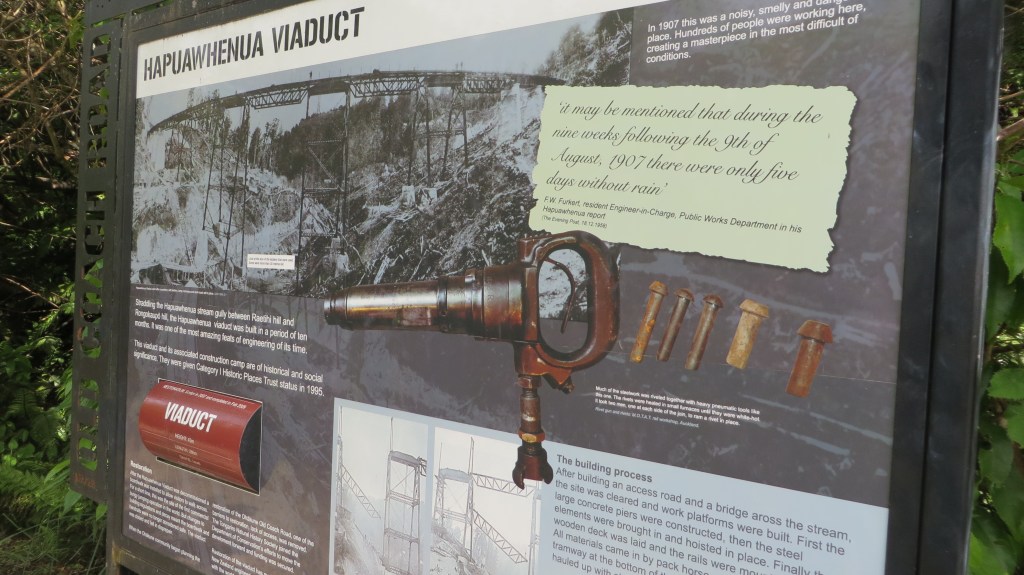

As the population grew so to did the need for actual roads, the name ‘old coach road’ is an obvious reference to an old road no longer in use. Roads, tracks and bridges all form the story of how people moved about the landscape. The railway made a late appearance and where no longer in use its route and any associated buildings add to the archaeological record.

Dump/midden sites – these are always found associated with a settlement or industrial site of some description. Often they are the only indicator that there was a settlement there at all (see my post on Fitzpatrick Bay here).

Conflict – here we can consider sites that relate to the various conflicts that have affected New Zealand over the years. In the 1800s wars with māori resulted in changes to pā construction (Ruapekapeka, Northland) and the creation of redoubts by European militia (Queen’s Redoubt, Waikato). In the early to mid 1900s there were various threats (perceived or otherwise) and a range of forts and coastal defences were constructed as part of this.

The above photos were taken on North Head, Devonport, Auckland – for more on this site read here.

That brings us to the end of our wee romp through some of the archaeological sites you might find in Aotearoa New Zealand. I hope you have enjoyed this read, feel free to check out some of my other posts.

Further Reading

Davidson J ‘The Prehistory of New Zealand’ (1984) – although over forty years old it is still a useful reference book if you can get hold of a copy.

Wilson J (ed) ‘From the Beginning’ (1987) another oldie but a goodie

Smith I ‘Pākehā Settlements in a Māori World – New Zealand Archaeology 1769-1860’ (2019)

King M ‘The Penguin History of New Zealand’ (2003) For serious history buffs…