A recent discovery (and purchase) of three booklets in a local charity shop is my inspiration for this post. Folklore, legends, customs and superstitions have always interested me and if it they have anything to do with my favourite place in the UK – Cornwall – all the better. Reading through them I became aware that perhaps on an unconscious level such stories may have influenced parts of ‘The Adventures of Sarah Tremayne’. In particular, the character of Nan who is a practitioner of the craft in her own very personal way; the West Penwith landscape and places such as Zennor and the great granite tors.

What follows is a brief look at some of these stories, but first an introduction to the person who recorded them over a hundred years ago.

In 1865 Robert Hunt wrote ‘Popular Romances of the West of England’ as a result of a period of convalescence where for ten months he wandered around Cornwall and up to the borders of Dartmoor listening to ordinary people and recording their stories. In his own words, “drinking deeply from the stream of legendary lore which at that time flowing as from a well of living water”. He recorded many interesting and quirky tales, some about giants, some about the fairy folk, some about the enigmatic megaliths and some about witches and magic.

As mentioned above, witchcraft and magic are very much part of my writing, thus for the purpose of this article lets look at some of these tales of witches in Cornwall…

Zennor Charmers

One of the first stories to grab my attention was the tale of the Zennor charmers – afterall, Sarah’s Nan lives in Zennor as did her ancestors. According to Hunt it is said that the men and women of this parish had the ability to stop blood, however fast it flowed. But it seemed that the charms were closely guarded secret and not even amongst themselves would be shared. People travelled from miles to have themselves or their children charmed for things such as ringworm, pains in the limbs or teeth and ulcerations. Hunt recorded that a correspondent of his wrote of ‘…a lady charmer, on whom I called. I found her to be a really clever, sensible woman. She was reading a learned treatise on ancient history. She told me there were but three charmers left in the west, – one at New Mills, one in Morva and herself’.

Charms are a common form of magic found in the relatively recent past, most have a religious element invoking angels and the use of holy water – possibly as a means of not upsetting the religious sensibilities of the community who would suffer their presence provided they were not openly subversive. Others use more natural elements such as the ash tree, the moon and even fire (ie candles) – a reflection of older pre-christian beliefs but still acceptable providing no harm was done. Their use is mainly used as a curative for various ailments or to find love. There are those that could be used to harm others but these are rare and fraught with danger as often such things have been known to rebound on the user in unimaginable ways.

Charmers (also sometimes called pellars) were the more acceptable face of magic – tolerated by the church and society in general – unlike the witch or sorcerer…

How to Become a Witch

Here we find that the mysterious granite rocks play a part.

“Touch a Logan stone nine times at midnight, and any woman will become a witch. A more certain plan is said to be – to get on the Giant’s Rock at Zennor Churchtown nine times without shaking it. Seeing that this rock was at one time a very sensitive Logan stone, the task was somewhat difficult” (Cornish Legends p27)

A Logan stone is simply put a large slab of granite which is perched so perfectly on top of another, with only a single point of contact, that it rocks when touched and does not fall. There are several examples of Logan stones in Cornwall, the most famous is found at Treryn Dinas, the headland beyond the village of Treen. This particular one features in our next tale of Cornish witches.

The Witches of the Logan Stone

In his descriptions Hunt speaks of the ‘wild reverence of this mass of rock’ by Druids and people of the past. But it is the peak of granite just south of the Logan Stone, known as Castle Peak that he tells has been the place of midnight rendezvous for witches. He refers to them as the witches of St Levan who would fly into Castle Peak on stems of ragwort, bringing with them the things necessary to make their charms potent and strong.

From this peak many a struggling ship has been watched by a malignant crone, while she has been brewing the tempest to destroy it; and many a rejoicing chorus has been echoed, in horror, by the cliffs around, when the the witches have been croaking their miserable delight over the perishing of crews, as they have watched man, woman and child drowning, whom they were presently to rob of the treasures they were bringing home from other lands.

Cornish Legends Robert Hunt 1865 p29

The latter paragraph seems to confuse the witches of St Levan gathering at a dangerous stretch of Cornish coast with a band of wreckers, the similarities are obvious. Perhaps the stories were spread by the those who would not wish for anyone to pay to close attention to a particular locale.

Pengersick

There are many tales told about Pengersick Castle near Praa Sands. It is particularly well known for its many ghostly stories, I myself have had several odd encounters in and around the castle which you can read about online at The Celtic Guide (Halloween edition 2014). Hunt however, wrote of the first Pengerswick and his desire to improve his familys status. It seems that an ‘elderly maiden’ connected with the very influential Godolphin family wished to marry the elder son, a match his father encouraged. Unfortunately, the son could not be swayed, even when love potions brewed by the Witch of Fraddam were used. Eventually she married the old Lord himself.

Now the witch had a niece call Bitha who had been called upon to aid the lady of Godolphin and her aunt with their spells on the son, however she fell in love with him too. When the lady of Godolphin became the Lady of Pengerswick she employed Bitha as her maid. Yet the lady was still infatuated with the son and soon this turned to hate and then jealousy when she saw him with Bitha. In her bitterness she attempted all manner of spells but Bitha’s skill learnt from her aunt kept him safe. Eventually, the young man left Pengersick only returning on the death of his father.

During his absence the mistress and the maid spent a great deal of time plotting and counter-plotting to secure the wealth of the old Lord. When the son returned from distant Eastern lands with a princess for a wife and learned in all the magic sciences, he found his stepmother locked away in the tower, her skin covered in scales like a serpent as a result of the poisons she had distilled so often for the father and the son. She eventually cast herself into the sea, ‘to the relief of all parties’. Bitha did not fare much better, her skin had become the colour of a toad due to all the poisonous fumes she had inhaled and from her dealings with the devil.

The Witch of Treva

Once upon a time, long ago, there lived at Treva, a hamlet in Zennor, a wonderful old lady deeply skilled in necromancy. Her charms, spells and dark incantations made her the terror of the neighbourhood. However, this old lady failed to impress her husband with any belief in her supernatural powers, nor did he fail to proclaim his unbelief aloud”.

Robert Hunt ‘Cornish Legends’ p42

All of that changed one evening when the husband returned to find no dinner on the table. His wife, the witch, was unrepentant merely stating ‘I couldn’t get meat out of the stone, could?’ The husband then resolved to use this as a way of proving once and for all his wife’s powers. He told her that if she could procure him some good cooked meat within the half hour he would believe all she said of her power and be submissive to her forever. Confident she couldn’t accomplish such a thing, St Ives, the nearest market town was some five miles away and she had only her feet for transport, he sat and watched as she put on her cloak and headed out the cottage door and down the hill. He also watched as she placed herself on the ground and disappeared, in her place was hare which ran off at full speed.

Naturally he was a little startled but sat down to wait, within the half hour in walked his wife with ‘good flesh and taties all ready for aiting’.

Trewa, The Home of Witches

Not to be confused by the previous Treva (both pronounced ‘truee’) this particular place is now known as Trewey Common. Situated high on the moor between Nancledra and Zennor, it is landscape dotted with the remains of the ever present mining industry sitting alongside great outcrops of granite, some used in the construction of ancient monuments. Hunt described the scenery as ‘of the wildest description’, he is not wrong – even the modern mind can run wild with imagination in the evening twilight or on a moody day when the sky is as grey as the granite.

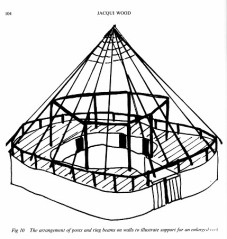

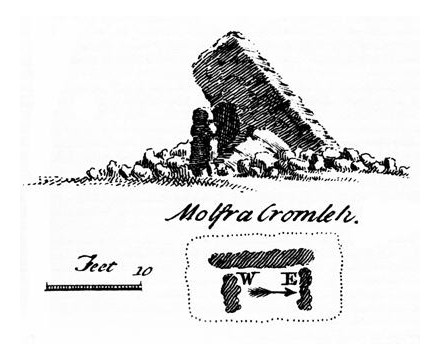

Hunt tells us that regardless of what local historians may say local tradition says that on Mid-summer Eve all the witches in Penwith gather here, lighting fires on every cromlech (quoit or tomb) and in every rock basin ‘until the hills were alive with flame’. Their purpose was to renew their vows to the ‘evil ones from whom they derived their power’.

It seems there was also another much larger pile of granite known as the ‘Witches Rock’ which no longer exists, having been removed quite some time ago. It was the removal of the rock which caused the witches to depart.

“…the last real witch in Zennor having passed away, as I have been told, about thirty years since, and with her, some say, the fairies fled. I have, however, many reasons for believing that our little friends have still a few haunts in this locality.”

R Hunt 1865 ‘Cornish Folklore’

Hunt did go on to say that there was one reason why all should regret the removal of the Witches Rock, it seems that touching the rock nine times at midnight was insurance against bad luck…

Cornish Sorcerors

Sorcerers were the male equivalent of the witch, however with the addition that the powers were passed from father to son (more a reflection of the patriarchal nature of society at the time).

“There are many families – the descendants from the ancient Cornish people – who are even yet supposed to possess remarkable powers of one kind or another.”

Robert Hunt 1865 ‘Cornish Folklore’

Unfortunately, apart from mentioning the family of Pengersick (which had by this time died out) and alluding to their wicked deeds he does not go into any great length about any of the other ancient Cornish families. Perhaps wisely, for if these unmentioned families did have remarkable powers it would not pay to offend…

Final Words

It is perhaps not surprising that certain parts of the Cornish landscape is given to fantastical tales of giants, witches and the fairy folk. The many ancient monuments, the craggy granite outcrops and the vast expanses of moorland lend themselves to an active imagination. The stories also serve as a caution against unchristian behaviour. As in the case of the witch of Treva who it is said when she died a black cloud rested over her house when everywhere else it was clear and blue. When the time came to carry her coffin to the churchyard, several unusual events occurred such as the sudden appearance of a cat on her coffin. It was only with the parson repeating the Lords Prayer over and over were they able to get her to the churchyard without any further incidents until they paused at the church stile and a hare appeared which as soon as the parson began the prayer once more gave a ‘diabolical howl, changed into a black unshapen creature and disappeared’.