Back in October the Auckland Council hosted the Auckland Heritage Festival, where, as the name would suggest all things heritage and Auckland was celebrated. There are a wide range of events during the festival weeks from walks, talks, exhibitions and workshops. I was able to attend two events – a talk at the Devonport Museum on Mt Cambria (more on that down the page) and a walk ‘n’ talk at Hampton Park.

Hampton Park is situated in the heart of commercial Otara, a pocket of farm land amongst the warehouses, factories and offices. Having never been there or even for that matter heard of it, I was intrigued to find out more. The park is in fact a working farm and whilst the public are able to walk around it there are no proper footpaths and no other facilities (there is a house and it is lived in by the family who farm the park as well others – if visiting please respect their privacy).

The story of Hampton Park begins long before people arrived in the area. Geologically it is part of the wider volcanic landscape of Auckland, here in Otara there are (or were) three volcanoes, the largest of which was called Te Puke o Taramainuku (‘the hill of Taramainuku’, a Tainui ancestor). The small scoria cone that sits in Hampton Park is the smallest of the three and is probably the smallest of all the Auckland volcanoes. It is so small that it has no formal name, simply being referred to as the Hampton Park volcano.

The beginnings of the human story in the area is much like the human story all over Tamaki Makaurau. Here like everywhere else Māori terraced the flanks of the cones and grew crops in the good volcanic soil. The larger cones would have provided a place of refuge when in need. The small cone in Hampton Park shows some evidence of terracing but later changes has blurred this somewhat. Alongside the driveway between the house and the church there is a large rectangular kumara pit which has remarkably survived. For more on the Māori use and occupation of the maunga of Tamaki Makaurau read here.

In 1852 the Rev. Gideon Smales, a Wesleyan missionary, bought 460 acres from the fencible Major Gray, settling there with his wife and children in 1855. The land was cleared of rocks, stone walls were built and crops and livestock brought in. Gideon Smales called the farm Hampton Park as he wished to model it on the English gentleman’s estate. It was said to have once rivalled Sir George Grey’s Kawau Island estate for its ‘botanical excellence’.

The farm grew oats, hay, barley, wheat and had an extensive orchard which included cider apple trees, pomegranates, oranges, figs and plums to name a few. In addition, to the more practical elements of the farm, the gardener – a veteran of the Crimean War – built a sunken garden in the form of the fort of Sebastopol. The remains of which can still be seen today. The excessive amount of stone on the estate resulted in it being used for a great many projects including the sunken garden, a rockery with a high stone wall and cave and of course the stone walls.

The stone walls which were constructed with the stone cleared away for cultivable fields was done so under the supervision of James Stewart who immigrated to New Zealand from Yorkshire. Due to the vast quantity of stone the walls were higher than was the norm and it was said there was over five miles of walls on the estate.

As is to be expected on a farm there are a number of buildings but perhaps the most striking are the remains of the stone stables, again built from stone quarried from the estate. Although not long after they were built a vagrant worker came to the estate looking for work, he was given a meal and allowed to sleep in the stables. That night the stables burnt down and the vagrant disappeared. They were never rebuilt properly although they were partly roofed over as barn and milking shed. Nearby are the derelict tin shed of the 1930s barn.

Two other buildings which still stand are the homestead and the church. The current homestead is the second to have stood on the estate, the first was burnt down in 1940 and the current homestead was built – only the front steps remain of the original house. The first homestead was built in 1855, it was three storied and had ten rooms which was later extended to eighteen rooms in 1869.

The small chapel – St John’s church – is also constructed using stone from a nearby quarry. Interestingly, the mortar for both the church and the house was made of burnt shell from Howick beach, the timber arrived via the Tamaki river and was brought overland by bullock teams. The first service to be held in the church was on Sunday the 12th January 1862. When the Rev. Gideon Smales died in 1894 he bequeathed the chapel and four acres jointly to the Anglican and Methodist Churches. It is still used today for services once a month.

The Missing Maunga

Beyond the settler history of the park there is another story that is reflected in the wider landscape of Auckland Tamaki Makaurau. As mentioned earlier the small volcano cone at Hampton Park is one of three in the immediate area, which may confuse the visitor, as nothing of the other two remain to be seen.

Te Puke o Taramainuku has been completely quarried away beginning in 1955 and now is vast expanse of factories, beyond is Greenmount or Matanginui which had minor quarrying from around 1870 which began in earnest during the 1960s. The quarry eventually became a landfill giving way to the gently sloping mound/hill we see today.

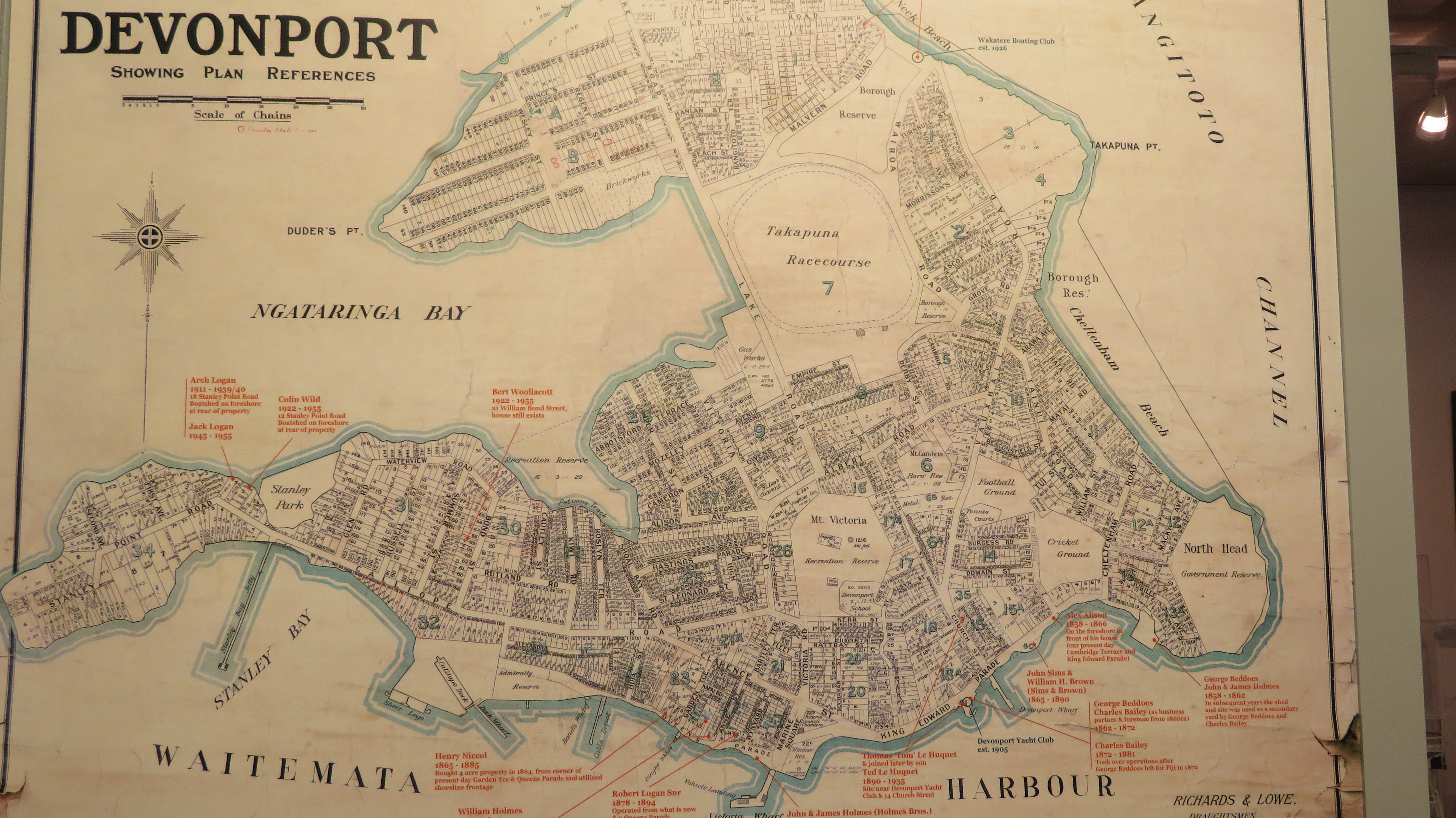

The quarrying of the volcanic cones around Auckland in the late 1800s up until the mid fairly recently was not an unusual. Many of the cities defining features were quarried away to make way for development and to use the raw material of scoria and basalt in the infrastructure of a city. An earlier event at the Devonport Museum told of the history of Takararo/Mt Cambria, another volcanic cone wedged between Takarunga/Mt Victoria and Maungauika/North Head which was mostly quarried away and only more recently became the pleasant parkland area it is today.

Other volcanoes that have been subjected to quarrying to the point of total removal include –

Te Apunga-o-Tainui/McLennan Hills; Waitomokia/Mt Gabriel; Ōtuataua Volcano/Quarry Hill; Maungataketake/Elletts Mountain; Te Pou Hawaiki (the second smallest cone and now a carpark);Te Tātua-a-Riukiuta/Three Kings; Rarotonga/Mt Smart; Maungarahiri/Little Rangitoto; Te Tauoma/Purchas Hill to name a few.

There are also many others which have been partially quarried, of the fifty three volcanoes in Auckland only thirteen appear to have been untouched by the bulldozer and the digger. This is not to say that those that remain have been completely untouched by human hands. For as long as there has been people in Tamaki Makaurau then the landscape and its features will have been adapted and utilised to suit the needs and requirements of its inhabitants.

For more information regarding the volcanoes of Auckland I recommend the following book –

B. W. Hayward (2019) The Volcanoes of Auckland. A field guide. Published by Auckland University Press

An example of some of the many terraces and platforms.

An example of some of the many terraces and platforms.

One of many defensive banks.

One of many defensive banks. Building platforms overlooking one of the volcanic craters

Building platforms overlooking one of the volcanic craters My daughter standing in one of the many hollows – possibly a storage pit for kumara.

My daughter standing in one of the many hollows – possibly a storage pit for kumara. A large midden suffering under modern footsteps.

A large midden suffering under modern footsteps. John Logan Campbell c.1880

John Logan Campbell c.1880

John Logan Campbell’s memorial to the achievements of the Maori people.

John Logan Campbell’s memorial to the achievements of the Maori people.