People have always been interested in the past, as far back as Nabonidus who ruled Babylon from 555 – 539BC who had a keen interest in antiquities to such an extent he even excavated down into a temple to recover the foundation stone which had been laid some 2200 years prior. Nabonidus also had a museum of sorts where he stored his collection. During the Renaissance those with the wealth to travel and collect began to keep cabinets of curios. In these you would find ancient artefacts displayed alongside minerals and natural history pieces.

“…the Renaissance attitude to the examination of the past…involved travel, the study of buildings and the collection of works of art and manuscripts.” (K. Greene 1983).

Initially it was classical antiquity which grabbed the attention of the well-to-do but after awhile eyes began to turn towards relics of their own past. The great stone monuments of North-western Europe became the immediate focus, places such as Carnac in Brittany and Stonehenge in Britain. Some of these gentlemen scholars would make systematic and accurate surveys of the monuments, which are still useful today, even if there were the less scrupulous who dressed up treasure hunting as scholarly research. These antiquarians were in essence the first archaeologists and their contributions can still be useful today.

In Britain several antiquarians stood out between the 16th and 18th centuries. John Leland (1503-1552) held the post of Keeper of the Kings Library and such travelled extensively throughout Britain. Even though his main interest was in genealogy and historical documents he also recorded non-literary evidence as part of his wider researches, one of the first to do so.

William Camden (1551-1623) learnt not only Latin but also Welsh and Anglo-Saxon in order to study place-names. At the age of 35 he published ‘Britannia’ a general guide to the antiquities of Britain. His descriptions of the ancient monuments are very detailed and he was one of the first to make a note of cropmarks and their possible links to sites no longer visible – an important part of aerial photography today. Camden was also interested in other forms of material culture such as pottery as a source of information on the past, a concept regarded eccentric at the time.

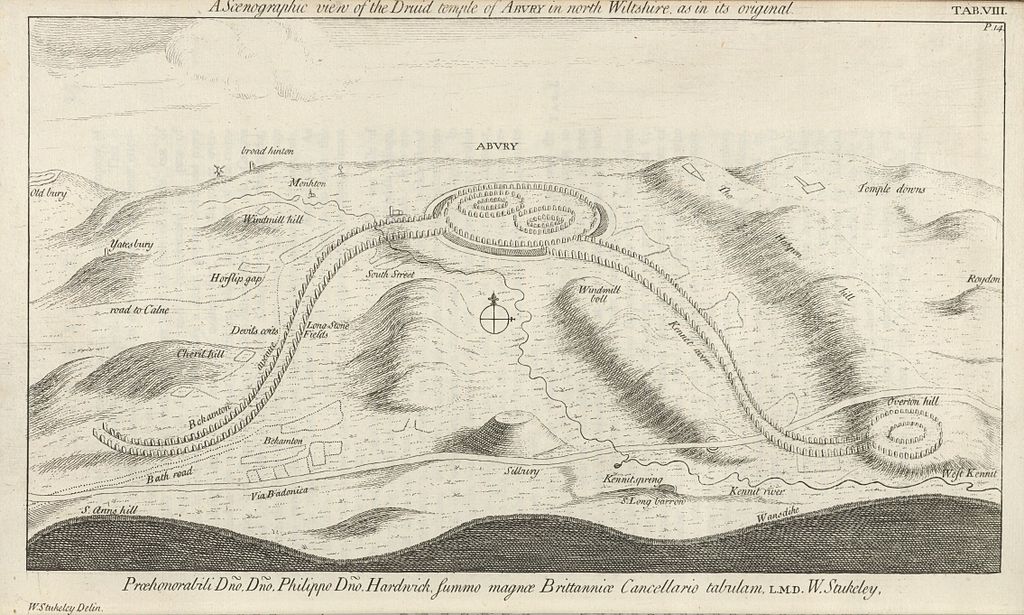

In the mid 17th century John Aubrey was one of the earliest writers to assign a pre-Roman date to sites such as Stonehenge, Avebury and Silbury Hill. His belief that such places were built and used by the Celts and Druids was so revolutionary there are still some who won’t let it go. Following in Aubrey’s footsteps was William Stukeley (1687-1765) who although trained as a physician spent a great deal of time conducting extensive fieldwork in Wessex during the 1720s. His highly accurate and detailed surveys of Avebury, Stonehenge and Silbury Hill are still used today. Stukeley’s recording of the avenue of stones (now destroyed) leading from Stonehenge to the Avon aided present day archaeologists in their search for them. However, in 1729 he was ordained and then attempted to use his fieldwork to establish a theological connection between the Druids and Christianity.

“Just as Dr Stukeley may be said to be the patron saint of fieldwork in archaeology, so can the Rev. William be held to be the evil genius who presides over all crack-brained amateurs whose excess of enthusiasm is only balanced by their ignorance of method.” (K. Greene 1983)

At the same time, across Britain, lesser well known antiquarians were busy studying and recording their own local areas. In the county of Cornwall this was no different. The earliest known antiquarian was Richard Carew (1555-1620) of East Antony, he was a member of the “The Elizabethan Society of Antiquaries” and in 1602 published his county history, “Survey of Cornwall”. Perhaps the most well known and often cited antiquarian was William Borlase (1695-1772) who like so many began collecting natural rocks and fossils found in the local copper works in Ludgvan where he was the local pastor. In 1750 he was admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Society and by 1754 he had published “Antiquities of Cornwall” which he then followed with “Observations on the Ancient and Present State of the Islands of Scilly and their importance to the Trade of Great Britain” in 1756.

Borlase’s great great grandson – William Copeland Borlase (1848-1899) – continued with the tradition of antiquarianism conducting some of the first excavations in Cornwall at Carn Euny in 1863. Copeland Borlase published many articles and books on the antiquities of Cornwall, including a two volume book titled “Ancient Cornwall” in 1871 and a year later “Naenia Cornubiae: a decscriptive essay, illustrative of the sepulchres and funereal customs of the early inhabitants of the county of Cornwall”. There were also a lecture on the tin trade and a monography on the Saints of Cornwall, not to mention a piece on the dolmens of Ireland and one on the mythologies of the Japanese.

William Copeland Borlase also spent a great deal of time getting his hands dirty excavating large numbers of barrows in Cornwall. He has been criticised for poor archaeological practice in only writing up a small percentage of those he excavated. Nothing makes an archaeologist bury their face in their hands then the lack of a written record for an excavation. Copeland Borlase often employed the services of John Thomas Blight (1835-1911) as an archaeological illustrator, although Blight was a well known antiquarian in his own right. He published two books regarding the crosses and antiquities of Cornwall, one for the west and the other for the east of the county.

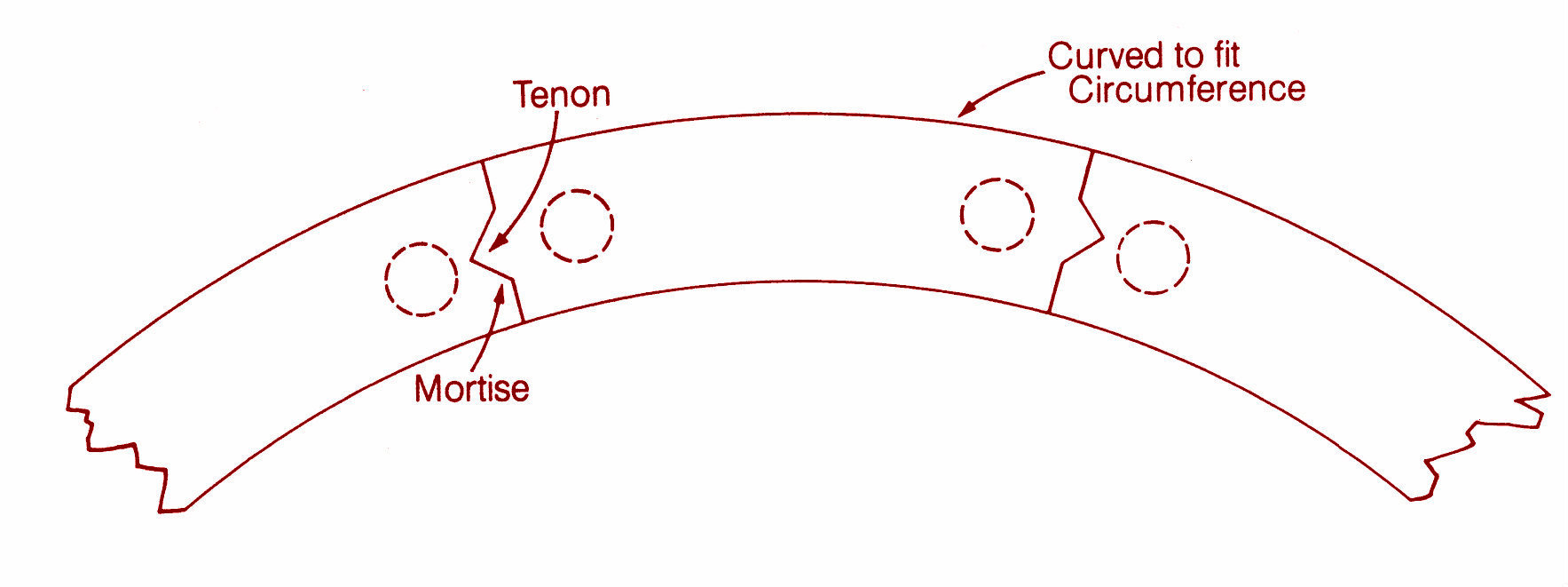

Blight’s drawings of Carwynnen Quoit were recently rediscovered by the lead archaeologist, Jacky Nowakowski, during her researches prior to the excavation and restoration of the quoit. In particular, the pencil drawing which had actual measurements was very useful in the interpretation of a stone pavement discovered during the excavation when combined with modern techniques. The archaeologists were able to get a better understanding of the positioning of the quoit within the Neolithic landscape.

Throughout the country there have been numerous societies which promoted the work of antiquarians beginning with the prestigious Royal Society. Even Cornwall had its own Royal Institute of Cornwall which is still operating today and currently manages the Royal Cornwall Museum as well as the Courtney Library which holds all manner of documents dating back into the 1700s. These early scholarly societies however, did not focus on one aspect of research, natural history, geology, botany and other gentlemanly pursuits were all encouraged. This attitude of open discourse across a variety of disciplines is one of the hallmarks of good archaeological research today.

Archaeology is defined as the “study of the past through the systematic recovery and analysis of material culture” (The Penguin Archaeology Guide). It is the recovery, description and analyse of material culture with the purpose of understanding the behaviour of past societies. Material culture is defined as anything which has been altered or used by humans – it can be as small as shark tooth with a hole drilled into it for a pendant or as large as a European cathedral. To study archaeology in general is to be a ‘jack of all trades and master of none’ – as a subject it borrows from history, anthropology, geology, chemistry, physics, biology, environmental sciences, ethnography to name but a few. Archaeologists have never been afraid of pilfering theories, methodologies and techniques from other disciplines.

The value of the early antiquarians does not necessarily lie in the outdated interpretations but in the production of often accurate and highly descriptive illustrations, field surveys and texts that are the basis of many manuscripts. Some of these ancient sites are now lost and/or destroyed, and the antiquarian illustrations are all we have as a record. Fieldwork will always be a fundamental part of archaeological work and the antiquarians of the past where the very first fieldworkers and the societies they belonged to provided the basis for the discipline of archaeology.

Green K. (1985) Archaeology – an Introduction. Routledge.

http://www.giantsquoit.org A website detailing the excavations and restoration of Carwynnen Quoit.