In this the second part of my small study of land use and settlement in the Upper Waitemata we are staying within the area defined in part one – from Island Bay to Kendall’s Bay, keeping within the coastal strip. This part will take a look at the early colonial/settler history of the area, with the emphasis being on the early or pre-WWII. After this point in time there is plenty of written records and several good books written on the history of Birkenhead and I have no desire to rehash already well-known information.

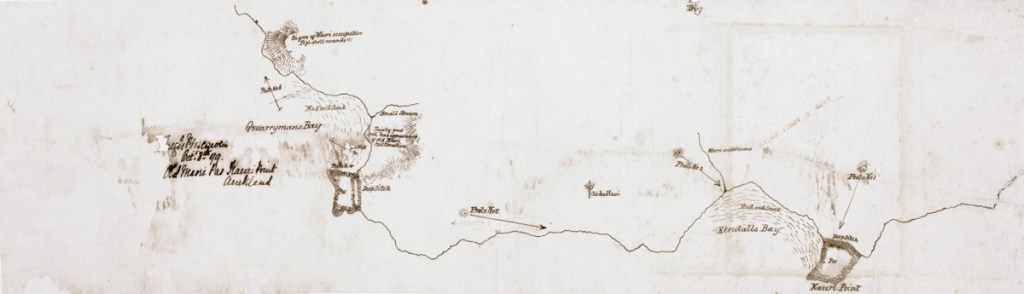

In 1769 Captain James Cook sailed through the Hauraki Gulf past Waiheke Island and made a note that there might be sheltered harbours to the west. The only other Europeans around at the end of the eighteenth century were whalers and as of yet no records have been found of any exploration into the upper Waitemata. It appears that it is not until 1820 that Europeans began to show an interest in this sheltered inland harbour.

Reverend Samuel Marsden is often credited with being the first to explore the area, in his diaries he states that he left the HMS Coromandel at Waiheke and was guided by Te Morenga to Riverhead where he then travelled overland to the Kaipara River – a route travelled by Maori for centuries.

During the next twenty years there were undoubtedly forays by other Europeans into the Waitemata, perhaps looking for timber and other such opportunities however their stories are as yet unknown. In 1840 the HMS Herald was the next major ship to visit the Waitemata, onboard was the Lieutenant Governor of NZ Hobson and the Surveyor General Felton Matthew. They spent the next two weeks exploring the harbour – Herald Island is named after the ship and of course Hobsonville after the Governor who had initially favoured the place as the capital of New Zealand.

Slightly further afield from our area of study there are records from around this time which make a note of sailors rowing up Hellyers Creek to a place called The Lagoon to restock their freshwater supplies, however, “it has also been recorded that in 1841 a Mr Hellyer, lived on the bank of the creek which now bears his name. He brewed beer which no doubt was a great incentive to those earlier seamen who rowed up the harbour…”

In 1841 our area of study was part of a large land purchase called the Mahurangi Block, it extended from Takapuna/Devonport to Te Arai and encompassed the majority of the present-day North Shore. The first parcels of land to be auctioned in 1844 were between Northcote and Lake Pupuke. Much of the early purchases in the Birkenhead area were part of a land speculation trend without the land being settled or farmed. Significant chunks of land sold were the area from Rangitira Rd/Beach Rd to Soldiers Bay which was sold to William Brown in 1845 and the area from Balmain and Domain Rds to the shore encompassing one hundred and ten acres being sold to a James Woolly also in 1845. However, it does not seem that either of them actually lived here. It was common practice for land to bought speculatively and sold on in smaller parcels to settlers fresh off the boat so to speak, such as the ‘Tramway Company’ a land development company who bought large tracts of land in what is now Birkenhead.

The earliest settlers of the Birkenhead area who are known were Henry Hawkins, Hugh McCrum, John Creamer, Joseph Hill, James Fitzpatrick and William Bradney. All of whom appeared to have had a go at farming but little else is known about them.

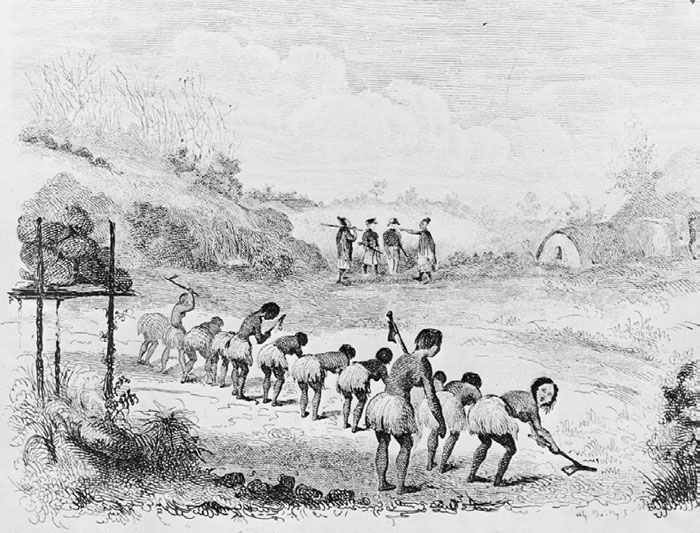

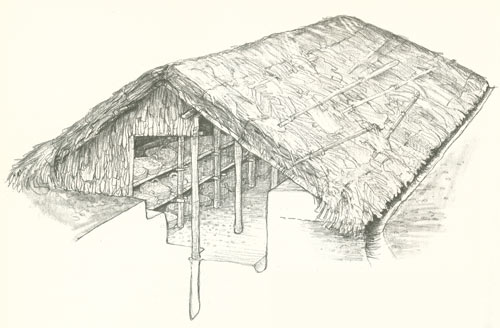

Unfortunately, those early settlers who chose the Birkenhead area were in for a hard time, as mentioned in part one the soil was not conducive to farming in the traditional sense. Settlement was a rather slow process particularly when compared to other parts of the North Shore and Auckland. Not surprising when faced with the prospect of clearing the bush before they could even build themselves a dwelling. Many of the early dwellings were simple one room nikau whares, constructed of sod walls with a raupo or nikau thatched roof. As they cleared the bush often deposits of kauri gum would be found and sold ensuring a source of income.

Even though most of these early farmers only managed a subsistence living, there were the occasional success story. Birkenhead became quite well known for its fruit orchards, the first of which was established by Henry Hawkins. There are two differing accounts as to where Hawkins had his orchard, some maintain it was near Soldiers Bay and others say it was on the ridge where Birkenhead Ave now runs. It is of course possible that both are correct, one of the earliest estates to be subdivided and sold was the Balmain Estate (also known as the Balmain Township) which extended over a much wider area than just the Balmain Rd of today. The steep sided valley of Soldiers Bay would appear to not be conducive to a fruit orchard, the thick kauri groves would have been quite a hindrance to say the least. However, an advertisement in the local paper for 1855 has H J Hawkins selling 700 fruit trees from his farm at The Glen, Soldiers Bay. Later in 1870-71 Hawkins is recorded as owning allotment two and three in Birkenhead – this is situated on the ridge which is now Birkenhead Ave.

Another early settler is mentioned in relation to a dwelling on a map dated to 1849, the house was owned by a John Crisp and was situated close to what is now Fitzpatrick Bay. Unfortunately, I have been unable to corroborate this.

According to a local history study of Island Bay and surroundings (Island Bay. A Brief History) there is an 1844 map which shows a dwelling occupied by a Mr George Skey. The bottom part of the block was developed into a small farm and sold as a going concern around 1849. It had its own jetty and a farm boundary ditch, unfortunately I have been unable to track down this map to verify this information and the area where the farm is said to be (and relatively well preserved) is part of the Muriel Fisher Reserve which is currently closed due to kauri dieback. Having said that, it is definitely something to consider and requires further investigation.

Whilst the 1880-81 electoral roll lists a small block (allotment 148 – a trapezoidal block which ran from what is now Rangitira Rd to the western edge of Soldiers Bay) of twenty-three acres owned by a Mr Clement Partridge who is described as a settler. The area of Island Bay was one of those places where early land sales were of the speculative kind. It wasn’t until the “Tramway Company”, a land development company, bought large tracts of land in the Birkenhead area including Island Bay, that small dwellings began to appear. Like many of the bays in the area, Island Bay was a summer place with the majority of dwellings being bach’s and only a handful were occupied all year round. The road began as a dirt track mostly used by gumdiggers and was previously known as Victoria Rd West prior to 1913.

What’s in a Name?

Placenames often hold clues as to the early settlement of an area and its changing history. In part one we already looked at some of the Maori names for places and how they relate to not only how the landscape was used but also how the people saw themselves within their world. For Europeans the naming of places can be a lot more prosaic and, in some cases, the reason for the name is obvious such as Island Bay, so named for the small island at the end of the road which was once separated from the mainland and only accessed at low tide via stepping stones.

Others, however, are much more difficult to ascertain – Kendall Bay is obviously a European name but at this point in time there are no records of anyone with the name of Kendall after whom the bay was so named. One possibility is that Kendall may be the name of gumdigger or gum buyer situated at the bay – gumdigger camps were often situated at the head of sheltered gullies near fresh water and near to the coast. Kendall Bay satisfies all of these requirements. Interestingly, the bay is also known locally as Shark Bay, undoubtedly because of the shark fishing grounds exploited by Maori and later Europeans.

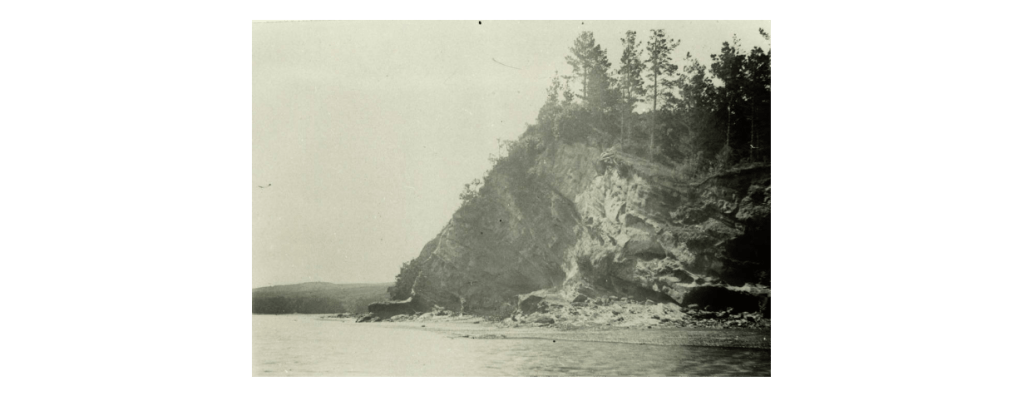

Interestingly, Kauri Point is the one placename not to change and to be consistently included in the majority of maps dating back to 1842 and up to the present day. It would be a fair guess to say the name came about as a result of the large kauri stands which would have been easily visible to the first people to sail up the harbour.

Names have also changed through time or have been forgotten. The Upper Waitemata was once called Sandy Bay on a nautical chart from 1841; another early map refers to Pt Shortland (1842), the headland where the Naval Base currently is; on other maps the bay we know today as Onetaunga Bay was once called Quarryman’s Bay.

Quarryman’s Bay, like Brick Bay further up the harbour, refer to the early industrial endeavours of the area’s inhabitants. Both quarrying and brickmaking were popular industries in a land where traditional farming was problematic. One of the occupations of a potential early settler in the area was brickmaker (see below).

Soldiers Bay is an interesting case of a name that has been around for a long time but its origins are hazy. The earliest mention that I have been able to track down is dated to a map of 1863. Today the stream that runs down from the high ground and empties into Soldiers Bay would have been a lot less silted up and most likely navigable by waka or rowboat as far as the present-day carpark. Today there is a causeway which joins the bottom of Balmain Rd to the reserve which would not have been there in the early days. This causeway was most likely constructed in the early twentieth century when a caretakes lived at the end of the reserve above Fitzpatrick’s Bay.

None of which gives us any clue as to why Soldier’s Bay is so named…it has been suggested that the bay gained its name as a result of an encampment of militia during the unsettled times of the mid-1800s. At the time, Hone Heke was ‘making life unpleasant’ for settlers in the north, particularly the Hokianga, and many had moved south to take up land in Birkenhead. To allay the fears of the settlers a contingent of soldiers may have been positioned in various places…hence Soldiers Bay. As mentioned before the stream would have been navigable to the bottom of present-day Balmain Rd, just before that though there is a flat spur which would have provided a good position for an encampment, with a clear view of the harbour and a fresh water supply.

The final placename to consider is that of Fitzpatrick’s Bay, this small sandy bay is today part of the Kauri Point Domain and is a popular recreational reserve for the local area. There are two possible people responsible for naming of the Bay – Charles Fitzpatrick or James Fitzpatrick.

An examination of Jury Lists and Electoral Rolls shows that a James Fitzpatrick arrived on the Jane Gifford in 1842 with his wife and daughter. The Jury List of 1842-57 lists James as living on the North Shore as a brickmaker; in the 1850s and 1860s he was still living on the North Shore but was now a farmer and a freeholder. Whether or not he was actually living in the Birkenhead area is difficult to say; Birkenhead itself was not so named until 1863 and up until that point there was very little distinction between areas. In the 1870-71 electoral roll James was listed as residing in Takapuna, allotment 15 – a survey of the cadastral maps of 1868 shows that allotment 15 is in fact in Northcote (Takapuna refers to Takapuna Parish of which included todays Takapuna, Birkenhead, Northcote, Hillcrest, Birkdale, Beachhaven and so on). In 1890, James was still in the Takapuna Parish but was now listed as a gumdigger.

Charles Fitzpatrick only appears twice in the lists; first in 1867 and as having a freehold land and house at Kauri Point however by 1890 he had moved to Morrinsville. Whilst only Charles is listed specifically as living in our area of study and he would appear to be the best option for the naming of Fitzpatrick Bay it is still not possible to rule out James.

Addendum

Not long after this post was written, I was contacted by a gentleman who currently lives south of Auckland near Hamilton. He was happy to confirm that James Fitzpatrick was indeed the correct person after whom the bay was named – James was his great great grandfather. He was also able to confirm that James did have a small brick kiln in the bay.

Fun in the Sun

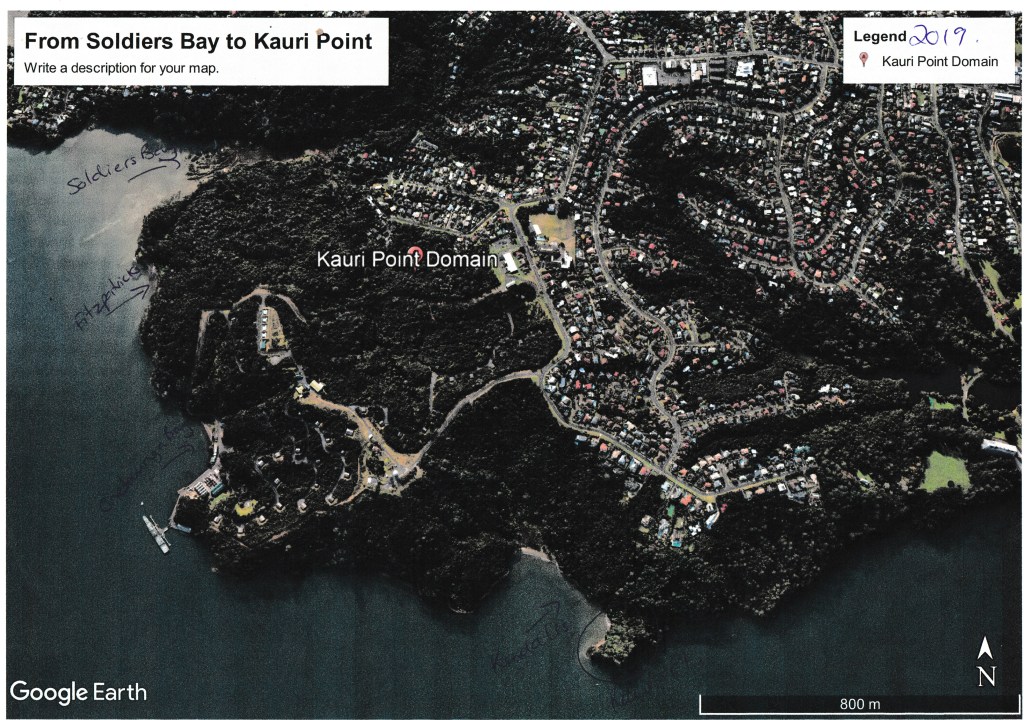

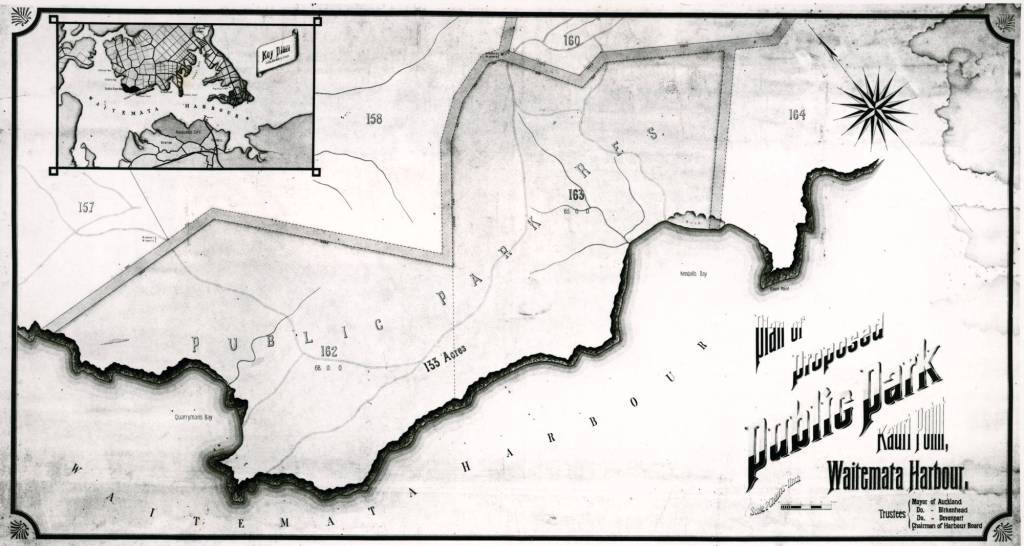

The study area today is made up of three different zones – residential (Island Bay), defence (Onetaunga Bay) and recreational (Fitzpatrick Bay, Soldiers Bay and Kendall Bay). In 1888 Governor William Jervois permanently reserved for the purpose of recreation 133 acres of land (allotment 162 and 163) in the Parish of Takapuna. It had been his hope that the area was turned into a national park, a place of tranquillity for Aucklanders. This was the area from Kendall Bay to the eastern end of Fitzpatrick Bay. In 1913 the Harbour Board acquired a further forty-two acres which included Kauri Point (allotment 164) which had previously been owned by Sir John Logan Campbell until his death in 1912. Further to this the area around Fitzpatrick and Soldiers Bay were then added to the park in 1916. An article in the New Zeland Herald in 1916 stated that the reserve had a fine waterfront and had in the past had been much used as a camping and picnic ground. It also mentions a ‘good five roomed house’, our first mention of what was to be known as the caretakers’ house.

An article from 1900 also in the New Zealand Herald also mentions how the Kauri Point Domain board had agreed to allow campers for a small fee. Interestingly they also denied a request for funds for a wharf. Reading through multiple articles the request for a wharf in the area is one which is constantly brought up, eventually a wharf was constructed but not at Fitzpatrick’s or Soldiers Bay but at Onetaunga Bay and it was paid for and built without the help of the board or their funds.

This marked a new era for this inner harbour landscape; each of the small bays were transformed in the summer months as families from the city side would spend the warmer days living under canvas. In the 1920s and 1930s there were seven or eight families holidaying at Kendall Bay, their camp was at the western end of the bay where there is a level space and a freshwater stream. At Fitzpatrick’s the camp site was at the northern end of the bay on the grassy area above the beach. Unlike elsewhere this part of the reserve was owned by the Birkenhead Borough Council from 1929 who improved it and put in place a caretaker.

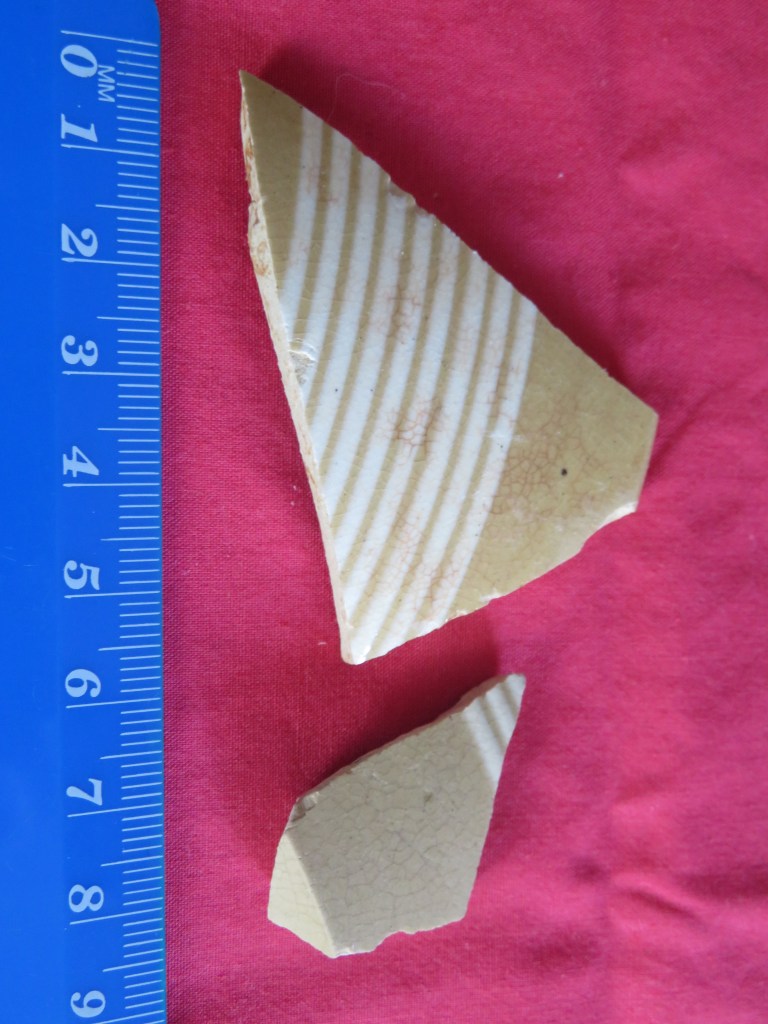

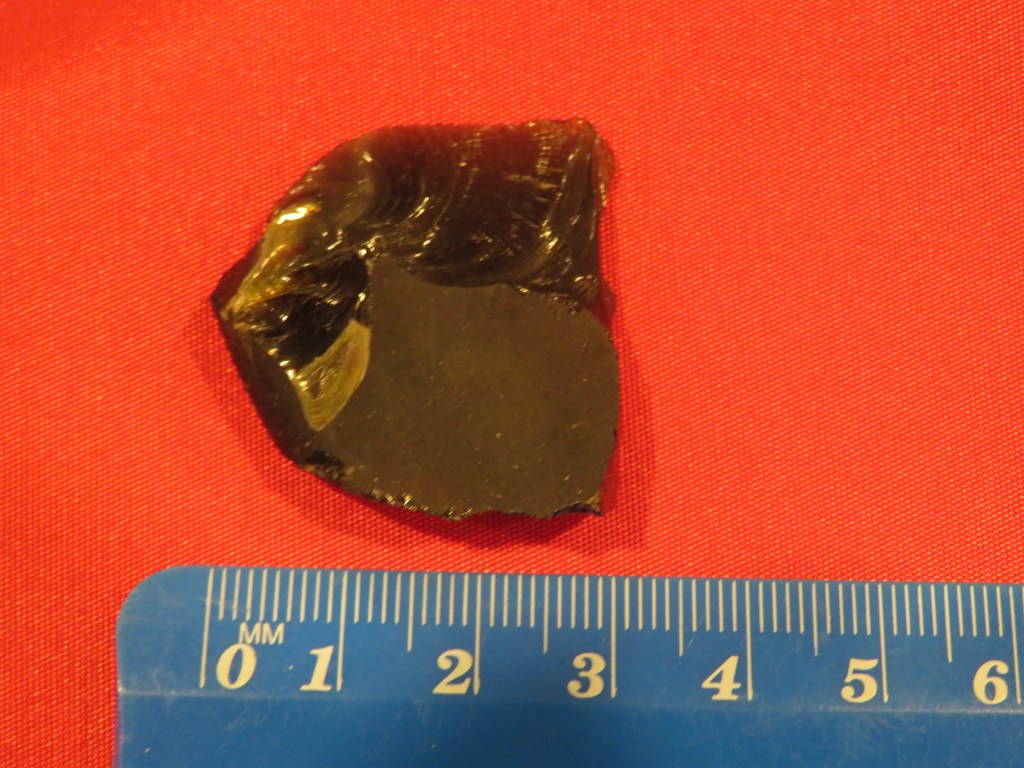

The only recorded caretaker was a William Henry Rickwood who lived in small house with his family on the hill above Fitzpatricks. Oral histories record how Williams’ wife would keep a small store selling sweets, soft drinks and other useful supplies. There was also a ‘ponga-house’ where Mrs Rickwood would provide hot water and often sold tea and scones to the visitors. There is very little that remains of this house today, just a level area with an overgrown collection of European garden plants such as figs and a rambling rose. However, there is evidence of both the campers and the caretakers in form of the rubbish they were throwing away. Often along the bay sherds of old ceramics dating from the late 1800s to the mid-1930s can be found, undoubtedly there is a European midden that has eroded onto the beach.

As well as the tent sites at Kendall Bay, there were other camping places, near the wharf at Onetaunga Bay and at Fitzpatricks bay which is the beach at the present Kauri Point Domain. Pre-World War Two and back through the Depression years, tents appeared each summer for a back-to-nature holiday by bush and sea. Much of the housework was left behind at home and there was no problem keeping the children amused. There were good sandy beaches and the harbour water was clear and clean in those days before the march of suburbia. (From a pamphlet of remembrances celebrating twenty years of Kauri Point Centennial Park, available in the Birkenhead Library).

Island Bay whilst listed as residential today was up until the construction of the Harbour Bridge mainly a summer town, full of bachs occupied only in the summer by families from across the water in the city. Unlike the other bays the land around Island Bay was owned by a land development company, being subsequently subdivided and sold off. However, because of issues of transport and roads only a few of the blocks were permanently occupied. Newspapers from the early 1900s often have articles describing summer outings by the Ponsonby Yacht Club to Soldiers Bay and area.

Defence

A final chapter in the history of land use in our area is that of defence. Just prior to the Second World War in 1935 ninety acres of the Kauri Point Domain was taken for defence purposes. The area of Onetaunga Bay (once Quarryman’s Bay) was developed for a storage facility for naval armaments. This unfortunately put paid to those carefree summer campers who no longer came in the large numbers, the caretaker at Fitzpatrick’s was still Mr Rickwood in 1938, as listed in the Wises Directory, but with the outbreak of WWII everything changed.

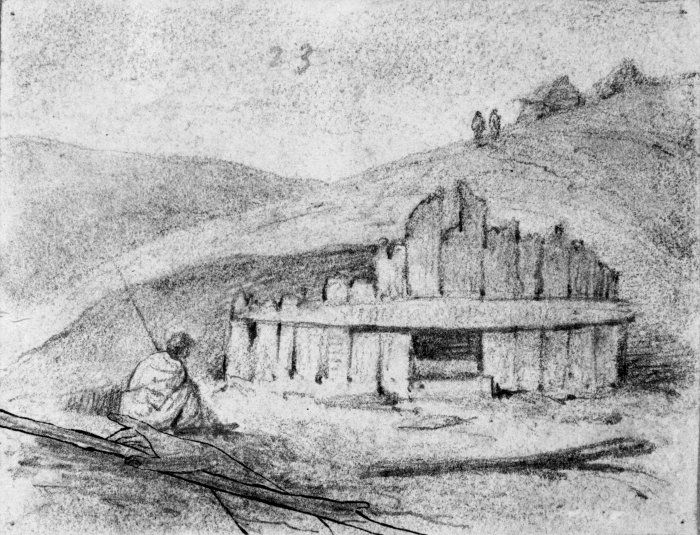

In 1942 the Americans had arrived in response to the Japanese threat in the South Pacific. Kauri Point Domain, Fitzpatrick’s bay included, were given over to the Americans and a large number of powder magazines were built. There are several unusual features on the beach at Fitzpatrick’s Bay, which may relate to these days.

After the war the Domain reverted to being parkland but never again were campers allowed back to any of the bays. Today the Naval depot forms a large wedge between Kauri Point Domain and Kauri Point Centennial Park.

Sources

McClure M (1987) ‘The Story of Birkenhead’

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections

‘Island Bay – A Brief History’ – unknown author.

‘Birkenhead The Kauri Suburb’

Papers Past – New Zealand

Electoral Rolls – Ancestry.com

‘Kauri Point Centennial Park Management Plan’ Birkenhead City Council 1989.

‘North Shore Heritage. A Thematic Review Report’ Auckland City Council 2011.