This article was originally written several years ago for the ‘Mythology Magazine’ which is now defunct. My intention when writing this was to look at some of the myths and legends associated with the colonisation of the Pacific so please do bear in mind this is not an academic treatise on this subject (that is a far too large a subject for a simple blog…).

The islands of the Pacific Ocean were one of the last places in the world to be colonised by people. The how, when and why has occupied archaeologists, anthropologists, linguists and historian for decades. For the European scientist these questions need to be answered with solid evidence backing them. For the indigenous populations tradition told them all they needed to know, the myths and legends providing all that was needed by the way of explanation.

New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter Island were the last landmasses to be colonised in the Pacific. These first peoples were at the end of a long line of ancestors whose collective knowledge fuelled their ability and desire to travel across vast tracts of ocean. The Pacific region is made up of three distinct areas – Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. The first area to have been settled by people was Melanesia; it consists of Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, the Solomon Islands, the Bismarck Archipelago and New Caledonia. Dates for the first colonisation range between some 50-30,000 years ago their ancestors originating from South East Asia. Micronesia is situated north of the Melanesian group and is made up of groups of islands including Kiribati, Nauru, Marshall Islands (to name a few) and the US territories of Guam, Northern Mariana Island and Wake Island. Evidence for the settlement of this region is difficult to pin down; the earliest archaeological evidence comes from the island of Saipan and is dated to around 3500 years ago. The third group of islands is Polynesia which covers a wide part of the Pacific. Generally speaking New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter Island form the corners of a triangle within which all other islands sit and are referred to as Polynesia.

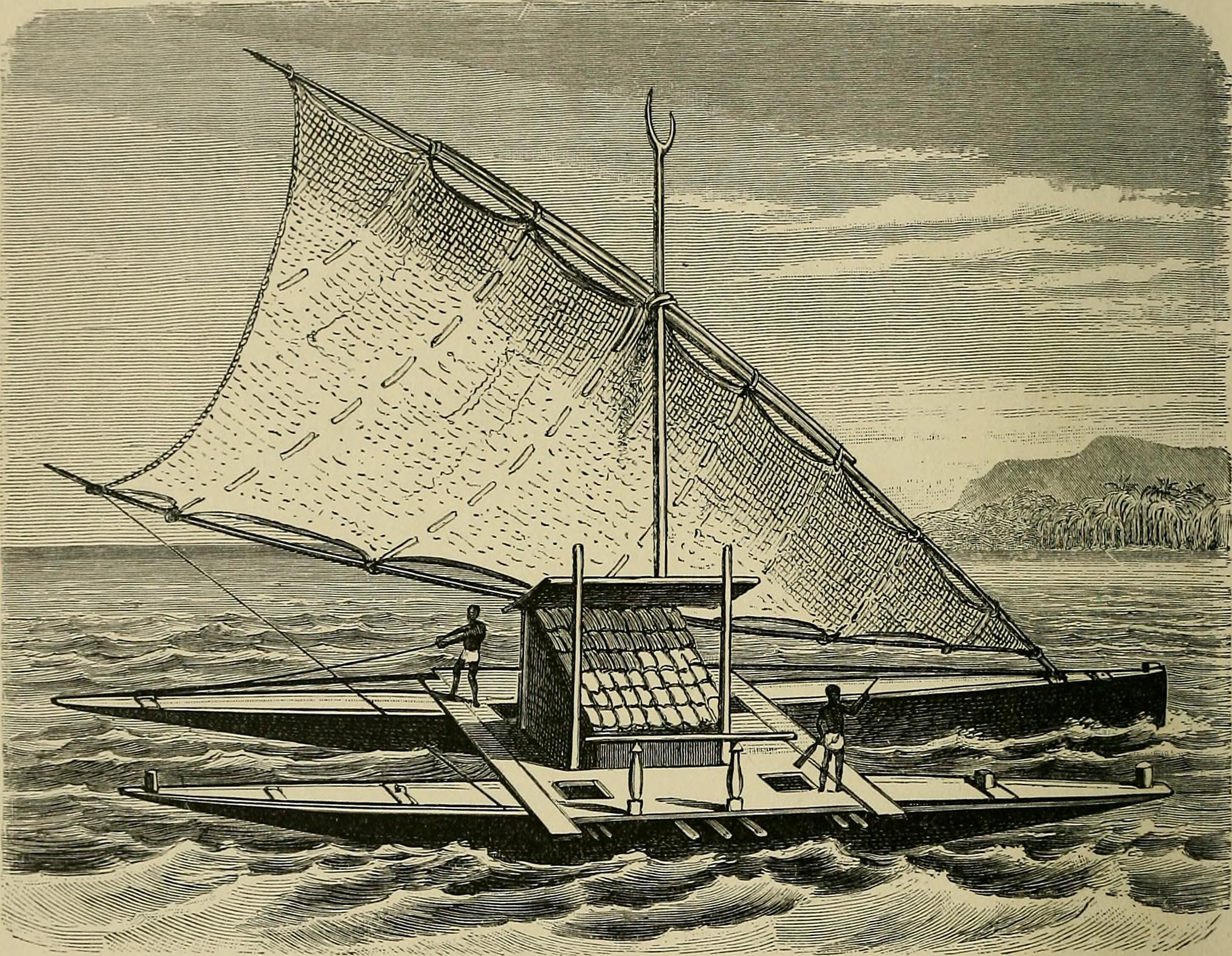

The ancestors of the Polynesians migrated from South East Asia a little later than the settlers of Micronesia, passing through some parts of Micronesia and Melanesia, but rarely settling for long. Fiji is an interesting case, as in many ways it straddles the line between Melanesia and Polynesia. When the ancestors of the Polynesians arrived in Fiji there was already a decent sized population and had been for millennia. Yet today the visitor to Fiji will see a multitude of faces, some are distinctly Melanesian looking (mainly in the eastern islands) and others look more Polynesian. Fiji in many ways was a jumping off point for the exploration further west, the next islands to be settled were Samoa and Tonga, both of which are not a great distance from Fiji. These early explorers are known as Lapita people based on a distinctive type of pottery found on the archaeological sites.

“All island groups in island Melanesia and West Polynesia that lie in a south-east direction have Lapita settlements. None of these settlements have been found on other islands.” (G. Irwin. Pacific Migrations – ancient voyaging in Near Oceania. Te Ara: The Encylcopedia of New Zealand.)

These people were exploring the region from as early as 3500 years ago (evidence found at the Bismarcks) and by 3000 years ago were already as far as Samoa and Tonga. The archaeology tells us these were small groups who travelled fast and light, they established only a few permanent villages on each major island group and then they moved on. At this time the distinctive Polynesian culture began to emerge in the west and by 2000 years ago people had begun to move into the eastern part of the region. By 700AD the majority of Polynesia had been settled with the last migrations being to New Zealand, Hawaii, Easter Island and South America (the only evidence for South America is the presence of the ‘kumara’ or sweet potato, radiocarbon dates from kumara found in the Cook Islands indicate that Polynesians had reached South America and returned by 1000AD at the latest).

All well and good you might say, but what has this to do with the mythology of the region? To study the past of this region it is important to not only use all those scientific tools we have at our disposal but also use the traditional knowledge, stories and myths to provide a greater depth of understanding. In Polynesia there are many stories which have a commonality suggesting a shared ancestry.

In much of eastern Polynesia Hawaiki (the Maori name) does not refer to the islands we know as Hawaii but to a mythical land where the ancestors journeyed from – an ancient homeland. In New Zealand nearly all the Maori have traditions of such a voyage, in the Marquesas it called Havai’i, in the Tuamotus it is Havaiki and in the Cook Islands the ancient homeland is referred to as Avaiki. Not only is Hawaiki the ancient homeland but it is also a place where a persons spirit would go after death. The main island of the Hawaii group is so named because it is the site of two volcanoes which were regarded as a place of great supernatural importance and the home of the gods. Similarly the island of Ra’iatea in the Society Islands was previously known as Havai’i and it too has a volcano on it (albeit a extinct one) believed to be the entrance to the underworld and the home of the gods.

In Maori myth Hawaiki is in the east – the direction of the rising sun and the stars which bring the changing seasons. Thus it is not surprising that Hawaiki was associated with life, fertility and success. It is said that the first human life was created from the soil of Hawaiki by Tane (or sometimes Tiki). It is the place of highly valued resources such as the kumara which is said to grow wild there – this is interesting in itself because if you travel directly eastwards from New Zealand you will (eventually) land in South America, the homeland of the sweet potato.

“When the ancestors arrived in their waka, they brought with them many treasured plants and birds, also important atua and ritual objects such as mauri. In one way and another, Hawaiki was the ultimate source of the mana of all these. The crops flourished, the gods exerted their powers, the mauri ensured continuing fertility of the resources they protected, because of their origin in Hawaiki.” (M.Orbell 1995 Maori Myth and Legend)

The veneration of the east – many rituals are conducted facing east – is unusual for Polynesia and has led some to make the dubious suggestion that New Zealand was settled by people from South America. More recent studies have demonstrated that the first voyagers would have taken a south-west trajectory from either the Cook Islands or the Society Islands in order to land on the east coast of New Zealand. Over time it would seem this navigational knowledge was amalgamated with the traditions of an ancient homeland.

In other parts of eastern Polynesia Hawaiki is in the west or sometimes even in the sky and in western Polynesia it is called by another name – Pulotu, a word that can be linguistically traced into Micronesia. It is interesting to note that the largest island that forms part of Samoa (western Polynesia) is called Savai’i and is a land associated in tradition with many supernatural goings on. Hawaiki was not only the land where the ancestors came from but also a place of spirits, a place where the myths came into being.

As time went on many of these stories would become absorb into local tradition with familiar places becoming the setting to the story. Thus the story of Maui who fished up the islands can be found everywhere in Polynesia. In New Zealand it is said that the North Island was a giant stingray fished up out of the sea by Maui using his magic hook (the hills and valleys of the land are a result of his brothers greed when they hacked at the fish). On the tiny atolls of Manikihi and Rakahanga it is believed that these islands are all that remains of a single land which broke apart when Maui leapt from it into the heavens. In Hawaii tradition tells of the islands being a shoal of fish and how Maui enlists the help of Hina-the-bailer to bring the shoal together with his magic hook to form one mass. Maui hauled on the line, instructing his brothers to row without looking back, which of course they did, this resulted in the line breaking and the islands become separated for all time. In the Tuamotaus Maui and his brothers are once more fishing far from land, once more he has a magic hook and once more he pulls up an island but because his brothers did not listen to Maui the giant fish/island broke apart and became the land the Tuamotua people refer to as Havaiki, where Maui and his family reside.

Maui is one of the most well known of Polynesian deities, found in the stories throughout the region he is often known as a trickster, part god and part human. He was of a time when the world was still new and there much to do to make it bearable for people. Maui is said to be responsible for raising the skies, snaring the sun, fishing up lands, stealing fire, controlling the winds and arranging the stars. On the island of Yap in Micronesia a demi-god figure called Mathikethik went fishing with his two elder brothers, he also had a magic hook and on his first cast brought up all sorts of crops, in particular taro, an island staple. On his second cast he brought up the island of Fais. The similarities here with Polynesian Maui are obvious and once again we can get a tantalising glimpse of past movements of people.

Other characters common to the stories of the Polynesia from Samoa in the west to Hawaii in the east include Hina, said to be both the first woman and a goddess who is the guardian of the land of the dead; Tinirau whose pet whale was murdered by Kae; Tawhaki who visited the sky and Rata whose canoe was built by the little people of the forest and was a great voyager and Whakatau the great warrior.

“…on every island the poets, priests and narrators drew from the same deep well of mythological past which the Polynesians themselves call the The Night of Tradition. For when their ancestors moved out from the Polynesian nucleus they carried with them the the knowledge of the same great mythological events, the names of their gods and of their many demi-gods and heroes. As time passed the Polynesian imagination elaborated and adapted old themes to suit fresh settings, and new characters and events were absorbed into the mythological system.” (R. Poignant 1985 Oceanic and Australasian Mythology).

Of course none of this addresses the question of why. Why did the first people leave their homelands and explore into the vast ocean, particularly to places like New Zealand, South America, Easter Island and Hawaii? What motivated them? The myths do in some way suggest possible reasons, these are stories people would have heard over and over again as they grew into adulthood. Stories of great adventurers, of those who dared to do the impossible and it does seem that much of the early migration was a result of simple human curiosity. Prestige and mana could be gained by person willing to find new lands. In the places they originally came from there was no food shortage and in some instances even once they had discovered a new island, they would move on leaving but only a small population behind. In the traditions there are also stories told of people being banished and having to find new places to live, in addition there are stories of battles lost and people fleeing retribution. These too could well be another window into the motivation behind Oceanic migration.

On their own the mythologies of the Pacific cannot provide us with more than a unique insight into the mindset of the peoples considered to be some of the greatest explorers of the past but when combined with genetics, linguistics and archaeology it gives us the ability to answer those questions of how, when and why.

Sources

Irwin G (2012) ‘Pacific Migrations – Ancient Voyaging in Near Oceania’ Te Ara: The Enclyclopedia of New Zealand.

Ratzel F & Butler A J (1869) History of Mankind

Poignant R (1985) Oceanic and Australasian Mythology

Orbell M (1996) Maori Myth and Legend