On a fine but crisp morning the family and I made the two hour journey to the set of Hobbiton where the scenes for the Shire were filmed for both the Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit movies. I am big fan of the works of JRR Tolkien and whilst I was dubious about the movies they still have much going for them. I was also dubious about visiting what is obviously a place with the overseas tourist in mind. However, I must admit to being pleasantly surprised – Hobbiton was delightful! The managment work hard to maintain the spirit of what Tolkien describes in loving detail. My visit was a balm to my frazzled self and the following are a few photos of our time there, I only wish we could have spent more time there.

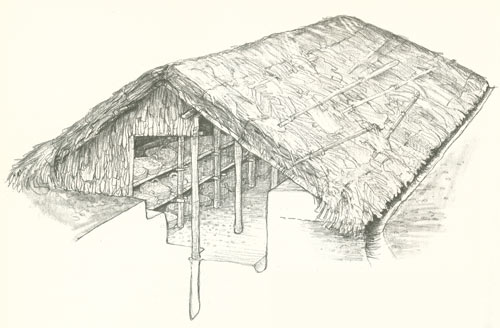

Hobbiton is situated on the Alexander farm near Matamata, Waikato and was first discovered during an aerial reconaissance for suitable filming locations for the Lord of the Rings trilogy. The original set was constructed of untreated timber, ply and polystyrene – it was always the intention to return the site to its original condition. However, with the filming of The Hobbit an agreement was struck between Peter Jackson and the Alexander family and Hobbiton was born, this time with more permanent materials.

The following are just a few of the many Hobbit holes, each individual in their own way with gardens and furniture. It seems as if the occupants have just stepped away and will be back in a tick…

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.” (The Hobbit. J.R.R. Tolkien).

Of course we were all looking forward to getting to the most important Hobbit hole of them all – Bagend…

“It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted gree, with a shiny, yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted…” (The Hobitt. J.R.R. Tolkien)

The oak tree in the picture above is an artificial tree made from steel and silicon with over 250,000 fake leaves…

From here our guide led us down to the Party field with its huge tree (this one is real and the reason for choosing this small part of the Waikato for a film set).

And then it was on over the bridge to the Green Dragon for mug of ale and food…

Two very happy hours later we turn and say goodbye to what can only be described as a magical place…

“By some curious chance one morning long ago in the quiet of the world, when there was less noise and more green, and the hobbits were still numerous and properous, and Bilbo Baggins was standing at the door after breakfast smoking an enormous long wooden pipe that reached nearly down to his wooly toes (neatly brushed) – Gandalf came by.” (The Hobbit. J.R.R. Tolkien)